Sunday, May 04, 2008

Cinco de Mayo Jokes: It's Really Not Funny

Here is another racist Cinco de Mayo comedy skit that makes fun of Latinos and distorts the holiday as "Cinco de Dos Equis." This is really not funny!

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Taking Back Cinco de Mayo

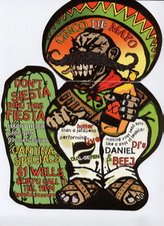

Youth are leading the way in taking back Cinco de Mayo. In San Diego youth are asking liquour stores and restaurants to not display offensive flyers about Cinco de Mayo. These teens are part of the Cinco de Mayo con Orgullo (with pride) Coalition, a statewide group that seeks to reclaim this holiday from the alcohol industry. The group has organized several alcohol-free, family-friendly Cinco de Mayo celebrations between May 2 and 6, including the Cinco de Mayo con Orgullo Para La Familia Festival at National City's Kimball Park.

Sunday, February 24, 2008

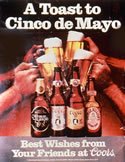

Cinco de Mayo and St. Patrick's Day

This video is another example of how U.S. marketers are linking Cinco with Mayo with St. Patrick's Day. While there are some similarities (expecially the alchohol industry's re-interpretation of these events as drinking holidays) there are important differences. One big difference is that Latino youth are disproportionally exposed to higher amounts of alcohol adverstisements than any other ethnic group (including Irish Americans). Another difference is the negative social stigma produced by Latino stereotypes within Cinco de Mayo advertisements further marginalizes and alienates an already stigmatized racial group that prevents it from advancing politically, educationally, and economically. Lastly, anti-immigrant groups have attacked the celebration of Cinco de Mayo in ways that St. Patrick's Day has not despite both groups having undocumented populations.

Sunday, August 12, 2007

Mocking Mexicans during Cinco de Mayo

Several weeks before May 5th 1994, a Michigan radio station offered listeners their “own personal Mexican” as the winning prize for a Cinco de Mayo contest. The radio dick jockey announced that, “Members of the station and their families are not eligible to own Mexicans—bathing and delousing of Mexicans is a winner’s responsibility. The station assumes no responsibility for infections diseases carried by Mexicans.”

The reading of this radio contest is that Mexican bodies, despite carrying infectious diseases and polluting the American body politic, are useful only for their “cheap labor” and after being exploited can be disposed at will. For radio shows and media advertisers Cinco de Mayo no longer represents a Mexican holiday commemorating the victory against French invaders, but a marketing opportunity to mock Mexicans for profit. Packaged commodified images and narratives of Cinco de Mayo are deployed and reinterpreted every year by corporations and advertisers to sell food and beverages products. To do this effectively they appropriate, refigure and resell images of Mexican history, tradition, culture, and language to establish closer market relationships between a particular product brand and consumers.

At the beginning of the new millennium there is no question that Cinco de Mayo has entered American mainstream. While many view this trend as a sign of progress, that is that Latino culture has finally reached national acceptance, others are more suspect and critical about its commercialization. The increase of immigration rates and high birth-rates among Latino/as has certainly contributed to the holiday’s popularity across the country. Cinco de Mayo celebrations can now be found in rather unexpected places in the East Coast, the South, Hawaii, and Alaska.

During springtime over five hundred cities across the United States organize a Cinco de Mayo celebrations. The largest of these and with high attendance and many sponsors include: Los Angeles’ Fiesta Broadway, Chicago South side’s Cinco de Mayo parade, St. Paul’s Cinco de Mayo in District del Sol, Denver’s Cinco de Mayo Celebrate Culture Festival, and Portland’s Cinco de Mayo Fiesta. The adoption of a Cinco de Mayo first-class stamp in 1998 and the 2001 celebration in the White House lawn were examples of its acceptance by the U.S. federal government. One geographer has even claimed that Cinco de Mayo has become more popular than St. Patrick’s Day.

Less understood, however, is the role of the marketing and advertising industry in using Cinco de Mayo to sell products to a growing Latino consumer market. In Latinos Inc., Arlene Davila shows how both Latino and non-Latino advertising agencies perpetuate stereotypical images of Latino/as and constructing a Latinidad that is commercially safe for consumption without challenging social inequities that continue to impact the Latino community. Some of these stereotypes included as exotic, family-oriented, hot and spicy food lovers, cultural traditionalist and hyper-nationalistic, being present-oriented and overly emotional, prone to listen to radio, watch television, but not reading, and fiercely loyal to name brands. These stereotypes are continually being reconfigured by marketing agencies to explain Latino consumer behavior and to tap into their “buying power.” The amount of goods purchased by U.S. Latinos increased from 1986 to 1996 reaching over $223 billion. According to a 2003 report by the Selig Center for Economic Growth at the University of Georgia the Latino buying power is expected to increase from 5.2% in 1990 to 9.6% in 2008. Another report estimated that Latinos currently spend $400 billion annually in the United States.

The alcohol and beer industry have been especially aggressive in spending millions in Latino advertising specifically targeting youth. According to a report by the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth at Georgetown University, Hispanic youth ages 12 to 20 saw and heard 20 percent more alcohol advertising in English-only magazines and on English-and Spanish-radio and television during 2003 and 2004 than young people in their age group. During the same years alcohol companies spent more than 3.5 million in advertising in both English-and Spanish-language media. As Paul Mendieta, director of Hispanic Marketing for Molson Coors Brewing Company, put it, “If you’re going to succeed in the beer business, you have to succeed in the Hispanic market.”

One of ways that brewers seek to succeed is by using Cinco de Mayo advertisements and event sponsorship. Mexican American community leaders bristle at the commodified images of Cinco de Mayo in television beer commercials, billboards, radio shows, store displays, restaurant and bar promotions that contribute to the racial stereotyping of Mexico and Mexican Americans. In response, community groups have organized their own alcohol-free celebrations calling them “Cinco de Mayo con Orgullo” (Cinco de Mayo with Pride) and proclaiming, ‘Our Culture in Not for Sale.’

The reading of this radio contest is that Mexican bodies, despite carrying infectious diseases and polluting the American body politic, are useful only for their “cheap labor” and after being exploited can be disposed at will. For radio shows and media advertisers Cinco de Mayo no longer represents a Mexican holiday commemorating the victory against French invaders, but a marketing opportunity to mock Mexicans for profit. Packaged commodified images and narratives of Cinco de Mayo are deployed and reinterpreted every year by corporations and advertisers to sell food and beverages products. To do this effectively they appropriate, refigure and resell images of Mexican history, tradition, culture, and language to establish closer market relationships between a particular product brand and consumers.

At the beginning of the new millennium there is no question that Cinco de Mayo has entered American mainstream. While many view this trend as a sign of progress, that is that Latino culture has finally reached national acceptance, others are more suspect and critical about its commercialization. The increase of immigration rates and high birth-rates among Latino/as has certainly contributed to the holiday’s popularity across the country. Cinco de Mayo celebrations can now be found in rather unexpected places in the East Coast, the South, Hawaii, and Alaska.

During springtime over five hundred cities across the United States organize a Cinco de Mayo celebrations. The largest of these and with high attendance and many sponsors include: Los Angeles’ Fiesta Broadway, Chicago South side’s Cinco de Mayo parade, St. Paul’s Cinco de Mayo in District del Sol, Denver’s Cinco de Mayo Celebrate Culture Festival, and Portland’s Cinco de Mayo Fiesta. The adoption of a Cinco de Mayo first-class stamp in 1998 and the 2001 celebration in the White House lawn were examples of its acceptance by the U.S. federal government. One geographer has even claimed that Cinco de Mayo has become more popular than St. Patrick’s Day.

Less understood, however, is the role of the marketing and advertising industry in using Cinco de Mayo to sell products to a growing Latino consumer market. In Latinos Inc., Arlene Davila shows how both Latino and non-Latino advertising agencies perpetuate stereotypical images of Latino/as and constructing a Latinidad that is commercially safe for consumption without challenging social inequities that continue to impact the Latino community. Some of these stereotypes included as exotic, family-oriented, hot and spicy food lovers, cultural traditionalist and hyper-nationalistic, being present-oriented and overly emotional, prone to listen to radio, watch television, but not reading, and fiercely loyal to name brands. These stereotypes are continually being reconfigured by marketing agencies to explain Latino consumer behavior and to tap into their “buying power.” The amount of goods purchased by U.S. Latinos increased from 1986 to 1996 reaching over $223 billion. According to a 2003 report by the Selig Center for Economic Growth at the University of Georgia the Latino buying power is expected to increase from 5.2% in 1990 to 9.6% in 2008. Another report estimated that Latinos currently spend $400 billion annually in the United States.

The alcohol and beer industry have been especially aggressive in spending millions in Latino advertising specifically targeting youth. According to a report by the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth at Georgetown University, Hispanic youth ages 12 to 20 saw and heard 20 percent more alcohol advertising in English-only magazines and on English-and Spanish-radio and television during 2003 and 2004 than young people in their age group. During the same years alcohol companies spent more than 3.5 million in advertising in both English-and Spanish-language media. As Paul Mendieta, director of Hispanic Marketing for Molson Coors Brewing Company, put it, “If you’re going to succeed in the beer business, you have to succeed in the Hispanic market.”

One of ways that brewers seek to succeed is by using Cinco de Mayo advertisements and event sponsorship. Mexican American community leaders bristle at the commodified images of Cinco de Mayo in television beer commercials, billboards, radio shows, store displays, restaurant and bar promotions that contribute to the racial stereotyping of Mexico and Mexican Americans. In response, community groups have organized their own alcohol-free celebrations calling them “Cinco de Mayo con Orgullo” (Cinco de Mayo with Pride) and proclaiming, ‘Our Culture in Not for Sale.’

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)